Listening to Serhii Hakman I am reminded of what Tony Judt wrote, paraphrasing Sigmund Freud:

"The Habsburg monarchy, the old Austrian empire thus had a double identity. More than anywhere else in Europe at that time, it was here that one was most likely to encounter overt prejudice on the Freudian principle of the narcissism of small differences. At the same time, people and languages and cultures were utterly intertwined and indissolubly blended in the identity of this place." (see Tony Judt with Timothy Snyder, Thinking the Twentieth Century, The Penguin Press, New York, 2012).

Listening to Serhii Hakman speak, I realize that in today's Bukovina, some things have not fundamentally changed, despite the many "waves" of history that have passed through there in just a century or so.

Serhii Hakman - let's take it slowly, we'll soon reveal who he is! - tells of his grandmother, Elizabet, who lived for more than ninety years. She was born in Austro-Hungary, married and raised her children in Romania, then raised her grandchildren and worked in a kolkhoz in the Soviet Union and died in independent Ukraine. Grandmother Elizabet did not travel much, living in the village of Ostrița, just beyond Chernivtsi on the right bank of the Prut river.

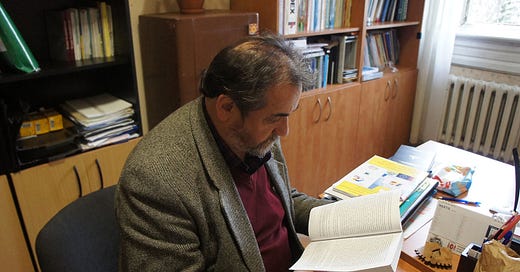

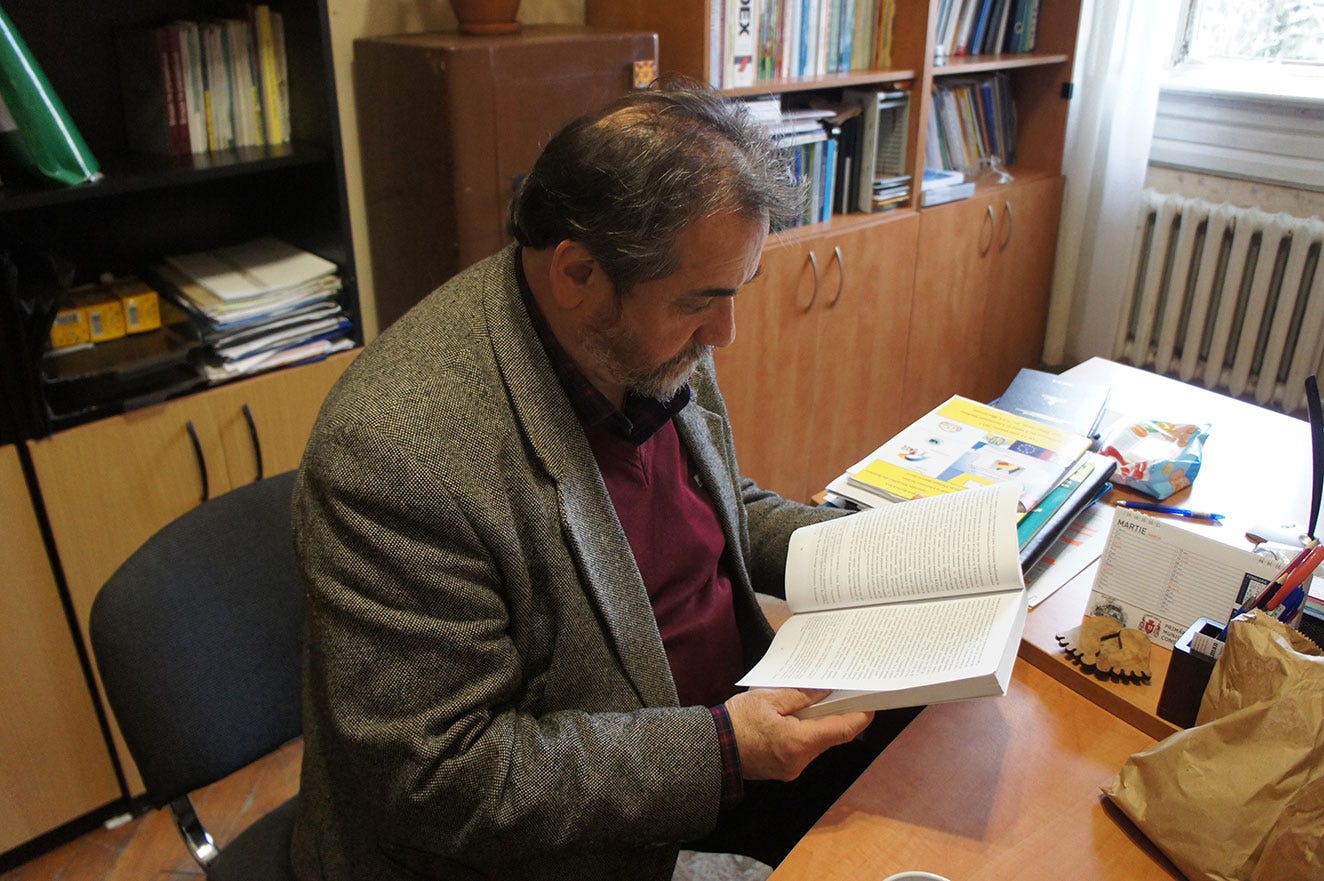

Unlike his grandmother, who experienced four changes in political regime and four changes in state language in her lifetime, Serhii Hakman experienced only two. He had to be a komsomolets (a member of the youth organization of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union), and for the past 30 years, he has worked as a civil servant in various Ukrainian state institutions. He is also a Ph.D. in history and a lecturer in political science and public administration at the University of Chernivtsi. He is also an ethnic Romanian.

"When someone asks me who I am, I say: I am an ethnic Romanian, but a Ukrainian political citizen. I am not a citizen of any other country and I consider myself a good Romanian and a patriot of the state where I live. This is my position, which I consider absolutely normal". Serhii Hakman's statement confirms that in Bukovina - a region where Austro-Hungarian, Romanian, Russian-Soviet, and Ukrainian administrations have succeeded each other in the last century or so - people, languages, and cultures are still strongly linked and inextricably amalgamated in the identity of this place.

"The only way for me to feel at peace in my heart is for my ethnicity and political nationality not to clash. Therefore, the only possibility is to build bridges and not fences between the two nations. I am very serious about different aspects of cross-border cooperation or whatever I can do in terms of Romanian-Ukrainian cooperation".

Serhii Hakman believes that the people of the two countries should learn more about each other - thus abandoning the open prejudices based on the Freudian principle of the narcissism of small differences - and this would mean an effort to promote each other's socio-economic initiatives, culture, literature, and shared history.

As for the rights of ethnic minorities, a subject that often inflames nationalist circles in Romania, Serhii Hakman believes that here too it's a question of achieving a balance between minority and Ukrainian rights. "People need to be able to study a sufficient number of hours in their mother tongue, otherwise they lose their identity, the opportunity to know their culture and language. At the same time, they must also study enough in the state language, otherwise they don't have enough chances to become integrated into society."

From September 1st, Romanian schools in the Chernivtsi region will increasingly be studying in the Ukrainian language, gradually leading to 80% of the students in pre-university classes (10th and 11th grades) being taught in the state language. "I think this is a mistake," says Serhii Hakman, "because at the age of adolescence, you need to study more in the mother tongue, because this is the only way for a person to develop his or her own identity (...) A young person with a rich vocabulary is more mature, has a higher standard of knowledge, and this standard will be imposed when he or she learns another language. So a person who speaks the mother tongue badly will also speak the state language badly".

Serhii Hakman believes that the Education Law, adopted in 2017, also took its current form because of the war, "which always radicalizes certain decisions". And simple and immediate solutions specific to crisis or war conditions are not appropriate for complex situations.

On the other hand, the war, Russia's invasion of Ukraine has brought people on both sides of the Romanian-Ukrainian border closer together. "Only now have they (Romanians) found out that, in fact, here, in our country, a war has been going on for nine years, not just since last year. (...) From the beginning (with the annexation of Crimea in 2014 - editor's note) we have been in a total war, not just a hybrid war, with the Russian Federation", says Serhii Hakman.

At first glance, the war is not at all visible in Chernivtsi. The city breathes softly, the majestic buildings in the old center are worn only by the passage of time, and people take to their daily burdens without ostentation as they walk along the cobblestone streets that are said to have been swept with roses on holidays long ago.

In Chernivtsi, the war is still present though, in the ubiquitous yellow-blue colors of the national flag, in the memorials dedicated to the soldiers-heroes who died in battle, and in the news, but mostly distilled in people's looks and words. Or, as I saw myself, in a long, unending, tight, and desperate, utterly devoid of heroism, but no less shattering embrace of a middle-aged couple on a city bus station platform, in which the military-clad man could not tear himself away from the endless embrace of his woman