Trecutul trece, problemele rămîn

Nu doar pentru că una dintre ilustrații a fost găsită la ”gunoiște”, ci și pentru că are de a face cu ”curățarea” de racilele trecutului, pun și aici un articol pe care l-am publicat pe Balkan Insight

Rooted in the communist era, the politicisation of education remains widespread in Romania, fostering a culture of cheating and deception that’s proving tough to root out, according to a Balkan Insight report.

Had she not been her father’s daughter, she would have been only a decent mathematician. But, as the daughter of Romania’s former communist dictator, Nicolae Ceaușescu, Zoia Ceausescu accessed the highest academic positions in the country.

The recent sale of her PhD thesis in a public auction in Bucharest raised not only interest from collectors of memorabilia.

It also stirred memories about how a corrupt and politicized regime could also destroy the reputation of the education system. Which, more or less, is the same situation in contemporary Romania.

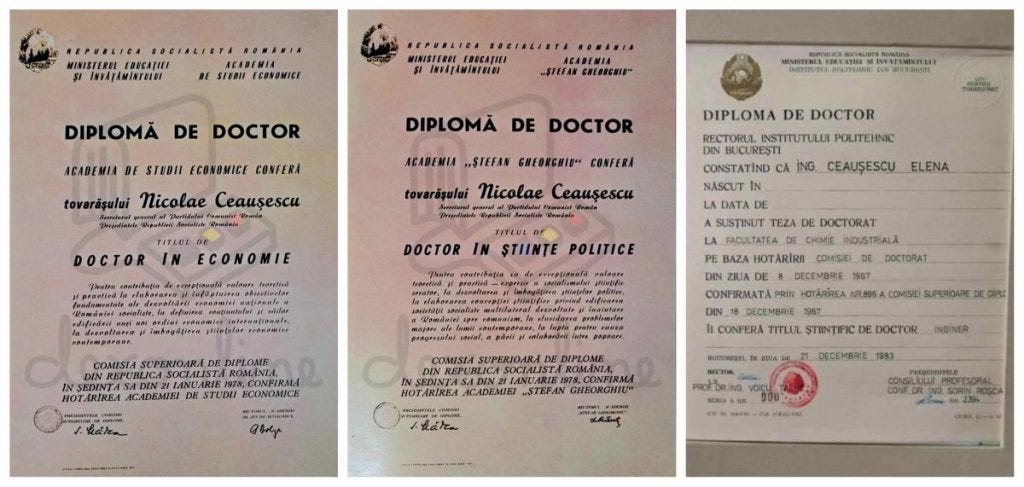

The Ceausescus are probably the family of politicians with the biggest number of PhD theses ever.

Dictator Nicolae acquired two, in Politics and Economy, his wife Elena one, in Chemistry, his brother Ilie, one, in Military History, while Zoia got one, in Mathematics.

“Starting from the early-1980s, the communist leaders in Romania tried to create an image of themselves not only as strong but also as educated persons, able to lead the country,” historian Cosmin Popa says.

“They did this by acquiring academic titles not on merit but as a result of the political subordination of the university environment,” he added.

Romania’s fearsome political police, the so-called Securitate, was tasked with getting recognition from academic institutions in the West for members of the Ceausescu family.

Elena Ceausescu forged an international reputation as a chemist, having many research articles published in scientific journals and getting academic recognition from reputed US and British institutions.

But there is plenty of evidence that her scientific career was bogus. “She was just an impostor who just put her name on papers written by Romanian specialists who were forced to do that,” Cosmin Popa says.

Nowadays, Romanian academics are still calling for Elena Ceausescu’s name to be removed from almost two dozen books and scientific papers published fraudulently as her own work.

Old ills in academia still present

Almost 35 years after the overthrown of Ceausescu regime, the situation in Romania’s education system has changed significantly, mostly for the better. But old problems such as cheating, plagiarism and bogus degrees are still plaguing schools and universities.

One particular situation in Romania is that after the fall of communism the number of universities, and thus of doctorates, ballooned.

In 1990, only 331 people obtained a PhD title. That number soared to 6,259 in 2012 before decreasing to an average of 2,200 per year since 2016.

Few of those who gained a doctoral degree did so to advance their academic career or for professional prestige. For many, the goal was a higher salary. Up to 2017, Romania was one of the few countries in the world where a PhD title meant a 15-per-cent pay rise in many professions.

Emilia Sercan, an investigative journalist and academic at the University of Bucharest, offers another reason for the huge number of PhD titles.

“In the mid-1990s, people at the beginning of their political careers … understood that an academic degree was necessary to gain easier access to the upper echelons of power,” Sercan told BIRN.

In their case, most often their academic work was plagiarized, as was often publicly revealed later on.

The revelations started with former prime-minister Victor Ponta in 2012. He was accused of plagiarizing much of his 2003 PhD thesis on the International Criminal Court. Three years later, the Ministry of Education stripped him of his law doctorate and he had to hand back his title after losing a court case.

Many other big names were exposed in the following years. Emilia Sercan did most of the work in this field. Since 2014, she has exposed over 50 cases of plagiarism, showing how a one prime-minister and other seven ministers, but also senior police officers and judges, broke the rules when publishing their books or PhD theses.

Her latest investigation is into the doctoral work of Interior Minister Lucian Bode, who allegedly plagiarized at least 18.5 per cent of his thesis. The university where Bode studied launched an internal analysis and confirmed Sercan’s findings.

Soon after publishing an article on this case last November, Sercan become a target of a smear campaign. According to a report of European Center for Press and Media Freedom, politicians from the ruling Liberal Party were instructed to publicly attack her, while articles attempting to discredit her were published by ghost media websites.

This is nothing new for Sercan. Four years ago she received death threats after revealing cases of plagiarism among professors from the police academy. A Bucharest court later sentenced the rector and his deputy, who put pressure on a subordinate to threaten her, to a three-year suspended jail term.

Sanctions process blocked

In recent years, some action was taken to tackle the problem of plagiarism in academia. Most universities started to acquire anti-plagiarism software that can detect similarities between submitted PhD thesis and their sources. They introduced mandatory ethics and integrity courses. Thesis are now evaluated more carefully and scrupulously.

But problems remain. Until recently, Romania have had a complex and lengthy process of sanctioning those proved guilty of plagiarism, who could even be stripped of their doctorate. Now even this process is blocked.

Surprisingly enough, Sercan is the cause of this blockage. “Following my investigations, the politicians did everything possible to make the process of withdrawing an academic title as complicated as possible and finally blocked it altogether,” Sercan told BIRN.

Last year, Sercan exposed plagiarism in the 2003 PhD thesis of the current prime minister, Nicolae Ciuca.

Ciuca, a retired four star general, rejected the accusations, saying he followed the academic rules of the time. But he also filed a civil case to appeal the complaints made against his alleged plagiarized thesis, which blocked any independent examination.

In June, the Constitutional Court stated that the Ministry of Education can withdraw a doctoral degree only under very specific circumstances or after a final court verdict, which can take years.

For Sercan, these measures are in fact an amnesty for all the people who cheated about their PhD thesis.

“Romania is facing a bizarre situation; we have people who have been proven as plagiarizing but they still keep a PhD title that cannot be withdrawn,” she notes.

But Sercan remains optimistic that the situation could improve if Romania closes legal loopholes and the academic community stays united in condemning academic fraud.

But the biggest problem is reducing the influence of politics in university life.

Historian Cosmin Popa agrees. “To put an end to the collapse of academic standards, politicians or their political accomplices have to be removed from the academic system,” he says.